Like all parties and major happenings taken place in the business side of the art world I had received a personal invitation for the next big event happening in London a couple of weeks ago. Art Fairs are excellent places to meet new people and involve oneself in future business perspectives. For some time one of the main topics in conversations was the party. Who would be there? Will it be a success? Who shall accompany me during the evening? Will it match other big parties happening around the globe? but, in particular, the one happening in London? What would this party be all about? Madrid tend to be more about food, friends and gossips; Basel it is, definitely, more heavy S&M; Paris the natural eloquence of the city; whereas the London Autumn party is more fashion and being in the viewing place. Normally, if I stay until the end it means the party has been a success; if I live through the evening it might mean that it was not so much. On the day, around 5pm, for my surprise, and even when it was only open for special invited people, the party was already busy. Strolling along the salon went to find my party, which was at the opposite corner, in the London First, from where I was standing. Some time after, G. and I, we decided to go for a walk and see where and what was going on. Fist stop the celebrities relaxing area. Dull place, definitely in need of great improvements in terms of unique sensorial experiences - will propose something far batter for it to L.W.! Since this was not the king of environment for people with our level of sensibility and interconnection with, we took our lead to the bar next door. A glass of champagne from a nearby private Partner while deciding where to go next, to go and see something worth viewing and be viewed and experienced: some paintings, some sculptures, a useful introduction to 2 photographers, from Manila, by B, from Austria, about the ideological conflicts between geographies, and so on. Until we found what we were looking for - naked woman, free drinks and food, music and drugs - at the bankers' and financiers' private party! It was 20h30 when someone kick us out. In the meantime H. had joint us. Whom, as G. has described, "...she's far too young for you, so hands off! and anyway I have some hopes in that dept...". Afterwards, our party went to the after-party at a claustrophobic underground pub in Mayfair.

Thursday 28 February 2013

Wednesday 27 February 2013

Monday 25 February 2013

Untranslatable Interpretations or Culturofagia: those who eat culture

In the Os Culturofagistas exhibition, there is a dislocation of similar elements, but used in a more disembodied way. Whereas this text has a strong underlying post-colonial theoretical approach to art and its reality and in how visual art statement informs about a particular social and cultural context in a globalised world. A tension is set up between the text's dominant idea and the deliberately separated elements that embody it, i.e. the exhibition, its works and its intention, and the text in itself. This serves different purposes. First, it acquaints the audience/reader with the full range of the story brought by the exhibition identity issues and it's intervinientes approach. Second, for the reader who knows the topic of "interpretation" and "intended and perceived meaning", it shows that the text is concerned with multiple ways in which the story in the exhibition has been used distinctively by artists, who, while having an international recognisable discourse, are able to show the difference between each other through their own individual reality. And, last, the text also implies a sequence that is a fiction constructed by the artist and/or viewer, since the apparent 'reality' is composed by the artist alone. Thus is, in fact, the real subject. The essay is not a dramatisation of the story told in the exhibition, instead it is about the nature of story and difference, as a construction over time and through cultures.

Artists participating in the project Os Culturofagistas (‘those who eat culture’) [Video: Os Culturofagistas retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kLzPBFzezw] use the Portuguese language as the starting point for their collaboration. Sharing the same common kernel–the Portuguese language–artists from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean engage in an exploration and interpretation of literary poetry in Samba and Fado, Brazil’s and Portugal’s traditional music, respectively. For the artists featured in the artistic project, emerging from different geographies, such as Latin America, Southern Africa and Occidental Europe (Márcio Botner & Pedro Agilson from Brazil, Délio Jasse from Angola and Sara & André from Portugal between many others), who use words spoken and written in Portuguese, the interpretation of Samba and Fado music’s lyrics is meant as a proposition to a future action, while creating one body constituted by works of art, not as a collective gathering of art works.

While both Samba and Fado “celebrate human beings and their passions,” [Castilho, M. and Oddo, E. (2012) Os Culturofagistas. Presentation paper (Personal communication, 2012)] Samba “is known for its irrepressible joy, even in daily life’s little sorrows, and celebrates the meeting of cultures.” With origins in Africa, South America, Asia, and Europe, it is also the “celebration of the arrival, of the meeting–the exaltation of the good that life can offer.” Fado, instead, is usually “associated with a certain nostalgia and the diaspora spirit,” it is about “departure, the uncertainties and fears that such adventure might cause–the uncertainty of fate.” This is an artistic project that informs through one singular context about two deeply interconnected cultures, Brazil and Portugal and Latin America and Occidental Europe on one level, and Christianity and Paganism, on the other. This doesn’t constitute an action or is an effect in itself. Each artist’s art work (video, photography and installation), for example, interfere with the other artists’ art work. It embodies the territorial act, becoming a one-artist show with multiple expressions, perlocutions on a particular condition, a proposed multiperspectival glance on cultural embodiments that act upon the idiosyncratic milieu within the international sphere. Primarily, the more than twenty artists featuring in the artistic project cannibalize on Samba’s and Fado’s written word, they ‘eat’ the work of others to conceive their own work.

What are exactly the normative meanings or references in the lyrics acted upon by Os Culturofagistas? How do such artists, such as, Sara & André (Lisbon, 1980 and 1979), cannibalize those meanings or references when they disembody the lyrics from Meu Lamento (written by Ataulfo Alves in partnership with Jacob do Bandolim) [Video: Meu Lamento retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xua2JeJZgr8]?

Juro... Confesso...Não faço verso

Para minha vaidade...

Meu samba é

O meu lamento,

Meu castigo meu tormento

Minha dôr minha saudade...

Por amar

Quase fracassei na vida

Por acreditar sincero

Em pessoa tão fingida...

As Stanley Fish argued “there are no determinate meanings and the stability of the text is an illusion.” [Fish, Stanley (1980) Is There a Text in This Class? In: A. Neill and A. Ridley (Ed.) (1995) The Philosophy of Art: readings Ancient and Modern. New York: McGraw Hill, pp. 446-457.] It is at this point that those artists, in Os Culturofagistas, aim to materialise their territorial creativity and inform about a particular condition of their everyday culture and life in general. They listen to words, to phrases uttered and, then, interpret them according to a set of conditions, values and determinacies shared with different members of the same community. How can we then make sense of the works other than its original intentions? “We will automatically hear [the utterance] in the context in which it has been most often encountered,” [Ibid.] because of the contextual setting within we are able to be, the wealth of cultural capital owned, and the vastness of our individual assembled repertoire–brought in at that precise moment and at the same time. For instance, when I "say" BNP, meaning the global bank, someone else might be convinced that I mean and refer to the British National Party, due to the context within which (s)he find herself or himself, which, also, might be distinctive, or not, from mine. In any of the situations brought about by the Os Culturofagistas, as a whole body of work, the meaning of the expression spoken would be severely constrained, not because it is heard ("perceive"), but because of the forms that it intends, in the first place, are heard ("understand:). The same can be applied to an artwork.

When referring to the lyrics, or, on another plane, to the artists’ expressions featured in the artistic project, meaning exists as a function, derived from the act of speaking or writing with regard to its purpose in a particular context. In Meu Lamento, for instance, the written words emerge in a situation and within that situation: for Samba music, to "celebrate human beings and their passions", in general, and "celebration of the arrival, of the meeting–the exaltation of the good that life can offer." It goes on to take as many interpretations as may people hear it! However, the lyrics of Meu Lamento emerge as a Samba through the interpretation instituted by several Samba singers. In the same form the lyrics emerge through the body of work brought by the Sara & André in the exhibition context: “the bohemian side common to Samba and Fado, as well as the intrinsic relation these two music genders have with popular festivities in both countries, Carnival, in Brazil, and Popular Saints, in Portugal” [Castilho, M. and Oddo, E. (2012) Os Culturofagistas. Presentation paper (Personal communication, 2012).]. [Video] The object of knowledge is distinctively read and listen, though; it is the performance manifested through the lyrics of Samba and Fado music, which are sang in and share the same common resource–the Portuguese language–in the artistic context of the Os Culturofagistas, that has been challenged–the criteria in which knowledge is attained. The disembodiment. In this context, the meaningful unit it combines is immediately corrected and preread, making another predetermination of the structure of interests from which the lyrics arise.

If the arts were used in the past as a field of conflict, nowadays, the sensation is quite similar. Having chosen a distinctive route from that taken by Asian or African artists and theorists, artistic creation and critical thinking in Latin America, in particularly in Mexico and Brazil, occupies a unique position on the modern and contemporary international art scene, with artists and theorists consistently linking international current events with issues of cultural identity. Making it a proper language. In Latin America, in 1928, the Brazilian modernist, Oswald de Andrade, called to the critical, selective and metabolising appropriation of European artistic tendencies, by artists from that continent, "anthropophagy’" or "cannibalism’"; later, in 1948, Cuban anthropologist, Fernando Ortiz, coined it as "transculturation’", which had an emphasis on resistance and affirmation of subaltern subjects; already in this millennium, Gerardo Mosquera, framed it as the "from here" paradigm, where artist from Latin America create “fresh work, by introducing new issues and meanings derived from their diverse experiences, and by infiltrating their differences in broader, somewhat more truly globalised art circuits” [Adler, P. et al. (Ed.) (2010) Contemporary Art in Latin America. London: Blackdog Publising, p. 16.]. The untranslatable interpretation of certain images into other cultural ideals could be regarded as going through the process of cannibalism, of being reterritorialized when the Western civilization structures of political imposition is replaced by the others’ structure of beliefs and rituals, i.e. the deterritorilization of Western ideals is then followed by reterritorialization in to Latin America's own system of beliefs and rituals, which can go beyond Pre-Columbus' world visions and life’ understandings.

Throughout the 20th century, artist creation in Brazil and Mexico has occupied a unique position on the international art scene with artists, from those countries, consistently linking and focusing on international political and social movements with issues of the country’s urban and political realities-the awareness of suburban and displaced popular cultural. In particular with the idea springing from the anxiety of not knowing their place in the world or being discarded as an error of European colonialization [Mesquita, Ivo (1996) Brazil. In: Edward J. Sullivan (Ed.) (1996) Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. London: Phaidon Press Limited. pp. 202-231.]. Brazil, for instance, has made important contributions to the dialogue engaged in by the international art community: the concept of Antropofagia, the São Paulo Bienal, the Neoconcretism movement, etc. Whereas, in Mexico, the Muralist movement, led by Siqueiros, Rivera and Orozco, in the beginning of the 20th century, and, most recently, contemporary art from Mexico, through the works of Carlos Amorales, Minerva Cuevas and Teresa Margolles [Video], for instance, influenced by internal political and social circumstances in fragmented Mexico, revindicate their position on the international art scene with a more global perspective and embedded in the world discourse. Nonetheless, “The formation of contemporary Brazil is different from that of other Latin-American countries” (Mesquita, 1996), including Mexico. Figuratively, Mexico reflects much of what has happened across the Spanish speaking countries in Latin America; essentially, due to a shared Spanish colonial past and impositions brought to that continent by the Catholic church. For more than four centuries, Latin American Spanish speaking countries tended to replicate, mimicking the impositions dictated from colonial Spain. While, instead, the same did not happen in Brazil. Portugal, throughout most of its history, was in a state of oblivion in regard to what was happening in the surrounding world, in general, and in the art debate, in particular. Just recently, only in the last two to three decades, and after internal social-political convulsions and external economical impositions, has started to have a voice in and to be heard by the international art scene. Whereas, instead, Spain has been one of the forerunners in artistic trends and impositions during its historical development. Throughout its history, Brazil has accompanied and has been at the forefront of the art discourse.

The act initiated by the Os Culturofagistas, proposed as a multidimensional perspective towards a relationship between Brazil and Portugal through their shared language, has an action as its aim, but that, in itself, does not effect or constitute an action. It is open to interpretation. Sara & André left empty bottles of water and wine, beer cans, cigarette butts lying on a dirty floor–remnants of what has happened. Was it a festivity? Was it an exhibition opening? The object is open to interpretation, but its meaning–that which is represented by the artwork and that which the author originally meant by her or his use of a particular sign sequence, either spoken or visual–is only understood by those who have knowledge of the word uttered. If not it will become an untranslatable interpretation. That is what most of the artworks are not! Including some of those in the Os Culturofagistas proposal, since some are or have been reduced to the artist’s intentions, while others are or have been irreducible to a minimal unit in the process of creating something, which cannot be diminished to the statements of intention that accompany it.

Published at VJIC: Journal on Images and Culture Issue 1, February 2013

Artists participating in the project Os Culturofagistas (‘those who eat culture’) [Video: Os Culturofagistas retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kLzPBFzezw] use the Portuguese language as the starting point for their collaboration. Sharing the same common kernel–the Portuguese language–artists from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean engage in an exploration and interpretation of literary poetry in Samba and Fado, Brazil’s and Portugal’s traditional music, respectively. For the artists featured in the artistic project, emerging from different geographies, such as Latin America, Southern Africa and Occidental Europe (Márcio Botner & Pedro Agilson from Brazil, Délio Jasse from Angola and Sara & André from Portugal between many others), who use words spoken and written in Portuguese, the interpretation of Samba and Fado music’s lyrics is meant as a proposition to a future action, while creating one body constituted by works of art, not as a collective gathering of art works.

While both Samba and Fado “celebrate human beings and their passions,” [Castilho, M. and Oddo, E. (2012) Os Culturofagistas. Presentation paper (Personal communication, 2012)] Samba “is known for its irrepressible joy, even in daily life’s little sorrows, and celebrates the meeting of cultures.” With origins in Africa, South America, Asia, and Europe, it is also the “celebration of the arrival, of the meeting–the exaltation of the good that life can offer.” Fado, instead, is usually “associated with a certain nostalgia and the diaspora spirit,” it is about “departure, the uncertainties and fears that such adventure might cause–the uncertainty of fate.” This is an artistic project that informs through one singular context about two deeply interconnected cultures, Brazil and Portugal and Latin America and Occidental Europe on one level, and Christianity and Paganism, on the other. This doesn’t constitute an action or is an effect in itself. Each artist’s art work (video, photography and installation), for example, interfere with the other artists’ art work. It embodies the territorial act, becoming a one-artist show with multiple expressions, perlocutions on a particular condition, a proposed multiperspectival glance on cultural embodiments that act upon the idiosyncratic milieu within the international sphere. Primarily, the more than twenty artists featuring in the artistic project cannibalize on Samba’s and Fado’s written word, they ‘eat’ the work of others to conceive their own work.

What are exactly the normative meanings or references in the lyrics acted upon by Os Culturofagistas? How do such artists, such as, Sara & André (Lisbon, 1980 and 1979), cannibalize those meanings or references when they disembody the lyrics from Meu Lamento (written by Ataulfo Alves in partnership with Jacob do Bandolim) [Video: Meu Lamento retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xua2JeJZgr8]?

Juro... Confesso...Não faço verso

Para minha vaidade...

Meu samba é

O meu lamento,

Meu castigo meu tormento

Minha dôr minha saudade...

Por amar

Quase fracassei na vida

Por acreditar sincero

Em pessoa tão fingida...

As Stanley Fish argued “there are no determinate meanings and the stability of the text is an illusion.” [Fish, Stanley (1980) Is There a Text in This Class? In: A. Neill and A. Ridley (Ed.) (1995) The Philosophy of Art: readings Ancient and Modern. New York: McGraw Hill, pp. 446-457.] It is at this point that those artists, in Os Culturofagistas, aim to materialise their territorial creativity and inform about a particular condition of their everyday culture and life in general. They listen to words, to phrases uttered and, then, interpret them according to a set of conditions, values and determinacies shared with different members of the same community. How can we then make sense of the works other than its original intentions? “We will automatically hear [the utterance] in the context in which it has been most often encountered,” [Ibid.] because of the contextual setting within we are able to be, the wealth of cultural capital owned, and the vastness of our individual assembled repertoire–brought in at that precise moment and at the same time. For instance, when I "say" BNP, meaning the global bank, someone else might be convinced that I mean and refer to the British National Party, due to the context within which (s)he find herself or himself, which, also, might be distinctive, or not, from mine. In any of the situations brought about by the Os Culturofagistas, as a whole body of work, the meaning of the expression spoken would be severely constrained, not because it is heard ("perceive"), but because of the forms that it intends, in the first place, are heard ("understand:). The same can be applied to an artwork.

When referring to the lyrics, or, on another plane, to the artists’ expressions featured in the artistic project, meaning exists as a function, derived from the act of speaking or writing with regard to its purpose in a particular context. In Meu Lamento, for instance, the written words emerge in a situation and within that situation: for Samba music, to "celebrate human beings and their passions", in general, and "celebration of the arrival, of the meeting–the exaltation of the good that life can offer." It goes on to take as many interpretations as may people hear it! However, the lyrics of Meu Lamento emerge as a Samba through the interpretation instituted by several Samba singers. In the same form the lyrics emerge through the body of work brought by the Sara & André in the exhibition context: “the bohemian side common to Samba and Fado, as well as the intrinsic relation these two music genders have with popular festivities in both countries, Carnival, in Brazil, and Popular Saints, in Portugal” [Castilho, M. and Oddo, E. (2012) Os Culturofagistas. Presentation paper (Personal communication, 2012).]. [Video] The object of knowledge is distinctively read and listen, though; it is the performance manifested through the lyrics of Samba and Fado music, which are sang in and share the same common resource–the Portuguese language–in the artistic context of the Os Culturofagistas, that has been challenged–the criteria in which knowledge is attained. The disembodiment. In this context, the meaningful unit it combines is immediately corrected and preread, making another predetermination of the structure of interests from which the lyrics arise.

If the arts were used in the past as a field of conflict, nowadays, the sensation is quite similar. Having chosen a distinctive route from that taken by Asian or African artists and theorists, artistic creation and critical thinking in Latin America, in particularly in Mexico and Brazil, occupies a unique position on the modern and contemporary international art scene, with artists and theorists consistently linking international current events with issues of cultural identity. Making it a proper language. In Latin America, in 1928, the Brazilian modernist, Oswald de Andrade, called to the critical, selective and metabolising appropriation of European artistic tendencies, by artists from that continent, "anthropophagy’" or "cannibalism’"; later, in 1948, Cuban anthropologist, Fernando Ortiz, coined it as "transculturation’", which had an emphasis on resistance and affirmation of subaltern subjects; already in this millennium, Gerardo Mosquera, framed it as the "from here" paradigm, where artist from Latin America create “fresh work, by introducing new issues and meanings derived from their diverse experiences, and by infiltrating their differences in broader, somewhat more truly globalised art circuits” [Adler, P. et al. (Ed.) (2010) Contemporary Art in Latin America. London: Blackdog Publising, p. 16.]. The untranslatable interpretation of certain images into other cultural ideals could be regarded as going through the process of cannibalism, of being reterritorialized when the Western civilization structures of political imposition is replaced by the others’ structure of beliefs and rituals, i.e. the deterritorilization of Western ideals is then followed by reterritorialization in to Latin America's own system of beliefs and rituals, which can go beyond Pre-Columbus' world visions and life’ understandings.

|

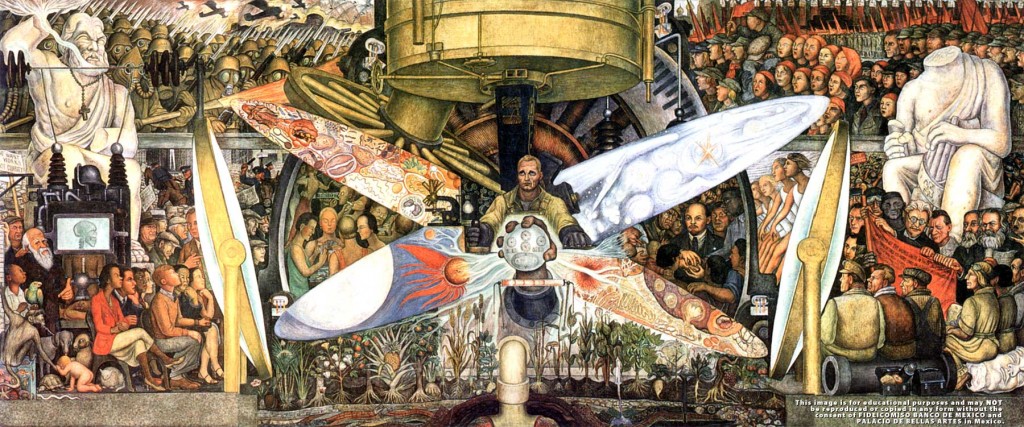

| The mural painted by Diego Rivera 'Man at the Crossroads' was repainted and renamed as 'Man, Controller of the Universe' at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.Diego Rivera. 'Man Controller of the Universe' or 'Man in the Time Machine'. 1934. Fresco, approx. 15' 10 7/8" x 37' 6 7/8" (4.85 x 11.45 m). Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS). Photograph by Schalkwijk/Art Resource, New York (USA) |

Throughout the 20th century, artist creation in Brazil and Mexico has occupied a unique position on the international art scene with artists, from those countries, consistently linking and focusing on international political and social movements with issues of the country’s urban and political realities-the awareness of suburban and displaced popular cultural. In particular with the idea springing from the anxiety of not knowing their place in the world or being discarded as an error of European colonialization [Mesquita, Ivo (1996) Brazil. In: Edward J. Sullivan (Ed.) (1996) Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. London: Phaidon Press Limited. pp. 202-231.]. Brazil, for instance, has made important contributions to the dialogue engaged in by the international art community: the concept of Antropofagia, the São Paulo Bienal, the Neoconcretism movement, etc. Whereas, in Mexico, the Muralist movement, led by Siqueiros, Rivera and Orozco, in the beginning of the 20th century, and, most recently, contemporary art from Mexico, through the works of Carlos Amorales, Minerva Cuevas and Teresa Margolles [Video], for instance, influenced by internal political and social circumstances in fragmented Mexico, revindicate their position on the international art scene with a more global perspective and embedded in the world discourse. Nonetheless, “The formation of contemporary Brazil is different from that of other Latin-American countries” (Mesquita, 1996), including Mexico. Figuratively, Mexico reflects much of what has happened across the Spanish speaking countries in Latin America; essentially, due to a shared Spanish colonial past and impositions brought to that continent by the Catholic church. For more than four centuries, Latin American Spanish speaking countries tended to replicate, mimicking the impositions dictated from colonial Spain. While, instead, the same did not happen in Brazil. Portugal, throughout most of its history, was in a state of oblivion in regard to what was happening in the surrounding world, in general, and in the art debate, in particular. Just recently, only in the last two to three decades, and after internal social-political convulsions and external economical impositions, has started to have a voice in and to be heard by the international art scene. Whereas, instead, Spain has been one of the forerunners in artistic trends and impositions during its historical development. Throughout its history, Brazil has accompanied and has been at the forefront of the art discourse.

The act initiated by the Os Culturofagistas, proposed as a multidimensional perspective towards a relationship between Brazil and Portugal through their shared language, has an action as its aim, but that, in itself, does not effect or constitute an action. It is open to interpretation. Sara & André left empty bottles of water and wine, beer cans, cigarette butts lying on a dirty floor–remnants of what has happened. Was it a festivity? Was it an exhibition opening? The object is open to interpretation, but its meaning–that which is represented by the artwork and that which the author originally meant by her or his use of a particular sign sequence, either spoken or visual–is only understood by those who have knowledge of the word uttered. If not it will become an untranslatable interpretation. That is what most of the artworks are not! Including some of those in the Os Culturofagistas proposal, since some are or have been reduced to the artist’s intentions, while others are or have been irreducible to a minimal unit in the process of creating something, which cannot be diminished to the statements of intention that accompany it.

© Rui G. Cepeda

London, December 2012

Published at VJIC: Journal on Images and Culture Issue 1, February 2013

Labels:

Culture

,

Culturofagia

,

Fado

,

Interpretation

,

Meaning

,

Samba

,

Text

,

VASA Project

,

VJIC

Sunday 24 February 2013

Friday 22 February 2013

City of Levallois Photography Award 2013

CALL FOR ENTRIES

City of Levallois Photography Award 2013

Open to all photographers aged 35 and under regardless of nationality

Win the 10,000 euros grant and the production of a solo show during the

6th edition of the festival...

image : Alexander Gronsky, from Mountains & Waters series, award-winner 2011

DOWNLOAD THE APPLICATION FORM:

www.photo-levallois.org

for more information:

info@photo-levallois.org

Win the 10,000 euros grant and the production of a solo show during the

6th edition of the festival...

image : Alexander Gronsky, from Mountains & Waters series, award-winner 2011

DOWNLOAD THE APPLICATION FORM:

www.photo-levallois.org

for more information:

info@photo-levallois.org

Thursday 21 February 2013

Sunday 17 February 2013

Thursday 14 February 2013

The London Art Book Fair 2013: Applications close 20 May 2013

The London Art Book Fair

13–15 September 2013

Applications close on 20 May 2013

13–15 September 2013

Applications close on 20 May 2013

The London Art Book Fair is an annual event at the Whitechapel Gallery where more than eighty exhibitors including galleries, magazines, colleges, arts publishing houses, distributors, rare book dealers and individual artist publishers meet to showcase and sell their work over a weekend dedicated to art publishing.

The next London Art Book Fair will take place at the Whitechapel Gallery on the 13–15 September 2013.

Please click here to apply for a stand.

Please click here to apply for a stand.

Tuesday 12 February 2013

On a Tuesday evening

What do you expect! I go through my preferred taverns in Mayfair or Shoreditch to find the best drink on offer. It could be an Italian sparkling Prosecco, a french established Champagne - my preferences go to Ruinart - a sponsoring beer brewery, or a cheep wine from the new country, like Chile, South Africa or Australia. The whole idea it to drink for free and get drunk in between, then get home and write words like these one. Objective and unromantic nonsense. If in the process I have some female company, the better, it always make me fell much more confident and reliable of my strength, or else it would be so deadly boring.

I don't believe in much of what people try to sell me, although much of the time I just try to be quite and do not say a word on the subject being discussed. They will disrail on the process. Artists, get away from them, or, then, them away from me! I just prefer bankers, doctors, marketing and PR people, landowners, evening ladies, politicians or Chefs. Much more pleasurable and the conversation, definitely, is much more thoughtful and hell raising.

Truly, in the art world, everything is so deceptive. Appearance is more important than Being. This world is just misleading! More, the art work dynamics' is in to give the wrong idea about someone and to someone, or the wrong impression about something, such as ideas, subjects, objects, etc. It gives the wrong information in order to bring a recognition of our limitations, in particular of one's thoughts. This world, in particular, belongs to a set of potentialities where meaning is genuinely ambiguous, since meaning can be used in similar contexts to mean both one thing and also its complete opposite, as was expressed in a recent conversation between Marlborough Contemporary' director, Andrew Renton, and artist' Jason Brooks, about his paintings done from photographs, which almost look like paintings rather than looking like photographs:

«Andrew Renton: And that finished item… when you stand back from it, does it surprise you? I’m asking because I always wonder how true to your sources you are – whether it’s a series of photographs or a found painting…

Jason Brooks: I’m responding to source material in the way Hockney responds to a landscape. I am not making a painting of a photograph. The goal is the finished work, I don’t judge it by its fidelity to any of its source material. To that end I’m always surprised – sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.»

So, to avoid confusion, I have a suspicious attitude - not nihilist - at the beginning and instead go and look for a better tavern and drink whatever their is to drink, except if it is beer or a lousy creepy wine. If in the meantime I don't learn something new, which will make me unlearn what I have accumulated throughout the last couple of decades of my life, add information and make me rethink about the surrounding structure, i.e., everyday life, it is just not worthy the hassle. In this case the objects on hold at the tavern deserved the drinks drank.

I don't believe in much of what people try to sell me, although much of the time I just try to be quite and do not say a word on the subject being discussed. They will disrail on the process. Artists, get away from them, or, then, them away from me! I just prefer bankers, doctors, marketing and PR people, landowners, evening ladies, politicians or Chefs. Much more pleasurable and the conversation, definitely, is much more thoughtful and hell raising.

Truly, in the art world, everything is so deceptive. Appearance is more important than Being. This world is just misleading! More, the art work dynamics' is in to give the wrong idea about someone and to someone, or the wrong impression about something, such as ideas, subjects, objects, etc. It gives the wrong information in order to bring a recognition of our limitations, in particular of one's thoughts. This world, in particular, belongs to a set of potentialities where meaning is genuinely ambiguous, since meaning can be used in similar contexts to mean both one thing and also its complete opposite, as was expressed in a recent conversation between Marlborough Contemporary' director, Andrew Renton, and artist' Jason Brooks, about his paintings done from photographs, which almost look like paintings rather than looking like photographs:

«Andrew Renton: And that finished item… when you stand back from it, does it surprise you? I’m asking because I always wonder how true to your sources you are – whether it’s a series of photographs or a found painting…

Jason Brooks: I’m responding to source material in the way Hockney responds to a landscape. I am not making a painting of a photograph. The goal is the finished work, I don’t judge it by its fidelity to any of its source material. To that end I’m always surprised – sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.»

So, to avoid confusion, I have a suspicious attitude - not nihilist - at the beginning and instead go and look for a better tavern and drink whatever their is to drink, except if it is beer or a lousy creepy wine. If in the meantime I don't learn something new, which will make me unlearn what I have accumulated throughout the last couple of decades of my life, add information and make me rethink about the surrounding structure, i.e., everyday life, it is just not worthy the hassle. In this case the objects on hold at the tavern deserved the drinks drank.

Monday 11 February 2013

Taryn Simon: The Picture Collection

Archiving systems impose an illusory structural order on the radically chaotic and indeterminate nature of everything.

—Taryn Simon

—Taryn Simon

Zhao Yao: Spirit Above All

Chinese artist Zhao Yao's first solo exhibition in the UK, featuring a series of paintings on denim embedded with the blessing of a living Buddha from Tibet. Did not got into the work, but really enjoyed the Italian sparkling wine - Spirit Above All

Thomas Joshua Cooper: Messages

John Ruskins' the principal role of the artist is "truth to nature"

|

| A Premonitional Work , The River Findhorn (Message to Timothy H. O’ Sullivan) Morayshire, Scotland, 1997-1999 Gelatin Silver Print Image: 43 x 60 cm, Mount: 71 x 91 cm |

Photos: A Premonitional Work (Message to Friedrich and Frith), Blaenau Ffestiniog, Gwynedd, Wales (Gelatin Silver Print, Image: 43 x 60 cm, Mount: 71 x 91 cm), 1992; Ritual Object (Message to Donald Judd and Richard Serra), Derbyshire (Gelatin Silver Print, 12 x 17 cm), 1975; The Promise of Apple Trees, (Message to Paul Strand and Agnes Martin) Galaestro, Santa Fe County, New Mexico, USA (Gelatin Silver Print, 16 x 23 cm), 1999/2000 - 2002. Courtesy: Haunch of Venison London.

José Parlá: Broken Language

Parlá's calligraphic abstractions are a record of the city as a living thing, a palimpsest of layers of human activity and meaning, a cacophony of histories, inscriptions and expressive gestures made by time and by humans.

Photos: Rajasthan Night Drive and Sign of the Times (Acrylic, gesso, oil, plaster, collage, ink on canvas, 121.92 x 182.88 cm (4 x 6 feet)), 2012. © Artist Rights Society, New York. DACS UK. Courtesy: Haunch of Venison London.

Sunday 10 February 2013

Saturday 9 February 2013

Sotheby's Contemporary Art Day and Evening Auction

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932WOLKE (CLOUD) signed, dated 1976 and numbered 413 on the reverse oil on canvas 200 by 300cm. 78 7/8 by 118 1/8 in. |

The present lot will be included in the forthcoming third Volume of the official catalogue raisonné, edited by the Gerhard Richter Archive Dresden, under no. 413, to be published in May 2013.

Provenance

Galerie Art in Progress, Munich

Schweisfurth-Stiftung Collection, Munich

Sale: Sotheby's, London, Contemporary Art Part I, 23 June 1999, Lot 31

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Exhibited

Hamburg, Kunstverein, Landschaftsbilder, 1989

Literature

Jürgen Harten, Gerhard Richter Paintings 1962 - 1985, Cologne 1986, p. 202, no. 413, illustrated in colour

Angelika Thill, et. al., Gerhard Richter Catalogue Raisonné, 1962-1993, Vol. III, Osternfildern-Ruit 1993, no. 413, illustrated in colour

Minoru Shimizu, 'Gerhard Richter' in: BT, no. 1, 2003, p. 130, illustrated

Catalogue Note

Emanating celestial light on a spectacular scale, the divine and immersive beauty of Gerhard Richter’s Wolke is utterly beyond reproach. Dislocated from terra firma, Richter’s fair weather fragment of sky is a masterwork of vaporescent forms and delicate sfumato brushwork. Radiating luminescent sunlit hues filtered through a harmonic miasma of soft ephemeral forms, this painting is undeniably indebted to a long and familiar legacy of art historical heritage. Readily evocative of the Romantic and sublime landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, John Constable’s famous cloud studies, the atmospheric light effects of Turner, as well as drawing on the cloud’s symbolic value as heavenly furniture in Renaissance and Baroque painting, the present work instantly conjures an encompassing transhistorical field of references, whilst remaining resolutely contemporary. Though drawing on a Nineteenth Century Romantic lineage and inescapably evoking a religiously loaded semiotic legacy, the artist’s fascination with clouds extends into an exploration of chance in painting - the ultimate expression of which was later refined from the 1980s onwards via the Abstrakte Bilder. Considered a deeply important facet in the encompassing trajectory of Richter’s career, many of the Cloud Paintings reside in numerous prestigious museum collections worldwide. Bearing a great similarity to Wolken (1970) housed in the Museum Folkwang, Essen, the present work’s formal and imposing beauty also rivals the National Gallery of Canada’s Cloud Triptych (1970), a work that recently formed a centrepiece in the touring Panorama retrospective. Representing the most pluralistic of thematic inquiries, the Cloud Paintings, more so than any other modality in Richter’s vast pantheon of subjects and media, forcefully straddles the readily drawn schism separating Richter’s abstract works from the hyperreal Photo Paintings. All at once, the stunning appearance of Wolke foregrounds religion, history and artistic inheritance within the complex debate for painting’s legitimacy in the later Twentieth Century.

Since the Medieval period and proliferate within the frescoed masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, clouds played a centrally decisive function in visually portraying the miraculous and divine - their vaporous forms withheld the potential for dissolving architectural boundaries to communicate the divine light of the infinite. Operating as the mid-point between the terrestrial and the celestial in countless frescoed church interiors, clouds are the traditional emblems for spiritual presence. As a subject of painting therefore, clouds are somewhat encumbered by a degree of cultural baggage – an aspect undoubtedly at stake within Richter’s series. Intriguingly, and perhaps somewhat indicative as to why the present work is so compositionally appealing, the harmonic arrangement in Wolke shares a pictorial equivalence to the asymmetrical balance of the most iconic work in the history of devotional art, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam (c. 1512). Indeed, across his corpus of Cloud Paintings Richter makes a direct concession to devotional tradition by employing the triptych format: multi-part works such as those held in the National Gallery of Canada and Essl Museum in Austria impart an organisational schema rooted in the history of the three-panelled altarpiece. Grouped with the corpus of Photo Paintings depicting vanitas subjects of candles and skulls initiated in 1982, it is clear that Richter invokes and confronts a tradition intended to orient the viewer away from the earthly to some spiritual higher realm. Richter identifies this in conversation with Benjamin Buchloh in 1986: “I do see myself as the heir to a vast, great, rich culture of painting – of art in general – which we have lost, but which places obligations on us. And it is no easy matter to avoid either harking back to the past or (equally bad) giving up altogether and sliding into decadence” (Gerhard Richter in: ‘Interview with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, 1986’, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ed., Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of Painting, London 1995, p. 148).

Growing up in Dresden, Richter would undoubtedly have been familiar with Caspar David Friedrich – Dresden was the city in which the father of German Romanticism established his reputation in the early Nineteenth Century. The atmospheric vapour, ethereal and mysterious effect pronounced by Richter’s Wolke finds immediate visual parity with the transcendental light-metaphors laid down within any number of works by Friedrich, such as Large Enclosure (1832) or Morning in the Riesengeberge (1810). Within the Twentieth Century the endeavours of Richter’s contemporaries to revive the genre of landscape, such as Lichtenstein’s comic book sea and cloudscapes or Blinky Palermo’s Minimalist abstractions, confer a somewhat anachronistic reading upon Richter’s romantic vistas in comparison. Though contemporaneous with Robert Smithson’s pioneering of Land Art, at first glance these works appear to share more in common with Constable’s masterful rendering of the sky or Turner’s treatment of atmospherics – ideologies rooted in specifically Nineteenth Century concerns with truthfulness to nature or an expression of the Sublime. Nonetheless, the subversion and contemporaneity of Richter’s works subtly operates within a remarkable double-speak. Speaking in 1986 Richter described his landscapes as “cuckoo’s eggs”, making explicit their inherently untruthful or misleading character (Gerhard Richter in: ‘Interview with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, 1986’, p. 163). Hubertus Butin critically expanded on this in 1994: “Richter’s landscape paintings do not go back to any religious understanding of Nature, for him the physical space occupied by Nature is not a manifestation and a revelation of the transcendental. In his pictures there are no figures seen from behind inviting the viewer to step metaphorically into their shoes or sink reverentially into some sublime play on Nature” (Hubertus Butin, ‘The Un-Romantic Romanticism of Gerhard Richter’, in: Exhibition Catalogue, Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Academy and FruitMarket Gallery; London Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, The Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790-1990, 1994, p. 462). By employing the sublime visual language founded in Friedrich’s pantheistic view and passing it through a mechanical photographic document, Richter systematically de-romanticises the genre, making it resolutely contemporary. This particularly stands for the Cloud Paintings. Executed and exhibited in series, these are not celestial clouds supporting divine figures or concealing an intimation of a heavenly beyond; though undeniably beautiful as a painted artefact, Richter’s clouds are indifferent, isolated, fragmented and evacuated of an emphatic human element.

Following the irreconcilable events precipitated in the first half of the Twentieth Century, Richter confronts the impossibility of continuity: by invoking the Romantic tradition directly, Richter looked to “make visible the caesura separating his age from Friedrich’s” (Ibid., p. 80). In 1973 Richter acknowledged this strategy: “A painting by Caspar David Friedrich is not a thing of the past. What is past is only the set of circumstances that allowed it to be painted: specific ideologies, for example. Beyond that, if it is ‘good’, it concerns us – transcending ideology – as art that we ostensibly defend (perceive, show, make). Therefore, ‘today’, we can paint as Caspar David Friedrich did” (Gerhard Richter, “Letter to Jean-Christophe Ammann, February 1973” in: Hand Ulrich Obrist, Ed., The Daily Practice of Painting, London 1995, p. 81). At first appearing incommensurate with contemporary practices of high-art, Richter’s detachment and evacuation of sentiment via the serial and mechanical, and its infusion with the vicissitudes of recent history, ensures a legitimate form of landscape painting that is also intensely beautiful. In Richter’s oeuvre clouds are emptied of their poignant Christian affect; historically evocative yet emotively absent, the intoxication and sublime wonder of God’s creation is replaced by the fragmentary and generalised: “Never spiritual, these totally secular clouds were rendered as merely divisible or repeatable motifs: minimalist clouds” (Mark Godfrey, “Damaged Landscapes” in: Exhibition Catalogue, London, Tate Modern, Gerhard Richter: Panorama, 2011-2012, p. 84).

As a minimalist motif, the cloud paintings also serve an intriguing and strikingly central function in Richter’s exploration of anti-painting and chance. Very much aligned with the Colour Charts and Grey Paintings - Richter’s most pronounced concession to Minimalism - the Cloud Paintings represent the perfect natural analogy for a repudiation of artistic, gestural or stylistic choices: “I pursue no objectives, no system, no tendency; I have no programme, no style, no directions. I have no time for specialized concerns, working themes, or variations that lead to mastery, I steer clear of direction. I don’t know what I want. I am inconsistent, non-committal, passive; I like the indefinite, the boundless; I like continual uncertainty” (Gerhard Richter, Notes 1964 in: The Daily Practice of Painting, Ed., Hans Ulrich Obrist, London 1995, p. 73). As an artistic mission statement, Richter is categorical in his determination for indeterminacy; what’s more by their very metamorphic configuration and vaporescent nature clouds as a subject represent anti-matter aspiring to form. In painting clouds from photographs Richter not only evokes Alfred Stieglitz’s photographic Equivalents (1927) in employing the cloud as a Duchampian readymade, but also selects a model from nature perfectly equivalent to the central impetus that would later drive the Abstrakte Bilder.

First initiated during the early 1970s simultaneous with the group of Photo Paintings of close-up paint swirls, Richter’s Clouds offered a natural model for the indefinite and utterly indeterminate; an equation no less inverted within the very nascent abstract works via their semblance of natural landscape – a precedent that would later confer naturally referential titles upon many of Richter’s abstracts, such as Rain (1988), Eis (1989) or Forest (1990). Speaking of the latter in 1990 Richter explained: “I want to end up with a picture I haven’t planned. This method of arbitrary choice, chance, inspiration and destruction may produce a specific type of picture, but it never produces a predetermined picture … by not planning the outcome, I hope to achieve the same coherence and objectivity that a random slice of Nature (or Readymade) always possesses” (Gerhard Richter, Notes 1990, in: Ibid., p. 218).

As both abstract forms and photorealist paintings, these works represent the most metamorphic and multidimensional of Richter’s career – significantly, it was this body of work that conceptually furnished and facilitated the artist’s transition into full painterly abstraction in the late 1970s. Visually defining ontological openness, the present work simultaneously stands among the most beautiful and stunning of Richter’s career whilst representing the most transgressive, symbolically redolent and conceptually pluralistic motifs ever translated by the artist into paint. All aspects of the artist’s philosophical, historical and aesthetic concerns are subtly concentrated into the glorious miasma and ethereal sfumato that constitutes Gerhard Richter’s Wolke.

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932ABSTRAKTES BILD signed, numbered 769-1 and dated 1992 on the reverse oil on canvas 200 by 160cm. 78 3/4 by 63in. |

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932ABSTRAKTES BILD signed, numbered 607-1 and dated 1986 on the reverse oil on canvas 70.5 by 100.3cm. 27 3/4 by 39 1/2 in. |

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932D.Z. signed, titled, dated 1985 and numbered 579-1 on the reverse oil on canvas 82 by 66.6cm. 32 1/4 by 22 1/4 in. |

Provenance

Denys Zacharopoulos, Paris (acquired directly from the artist)

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Exhibited

Paris, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Gerhard Richter: Painting, 1993

Bonn, Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Gerhard Richter: Painting 1962-1993, 1993-1994

Stockholm, Moderna Museet, Gerhard Richter, 1994

Bignan, Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Centre d'Art Contemporain, Praxis, 1994

Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Gerhard Richter, 1994

Literature

Exhibition Catalogue, Düsseldorf, Stadtische Kunsthalle; Berlin, Nationalgalerie Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz; Bern, Kunsthalle; Vienna, Museum Moderner Kunst, Gerhard Richter Paintings 1962-1985, 1986, p. 333, no. 579-1, illustrated in colour

Angelika Thill et al., Gerhard Richter Catalogue Raisonné, 1962-1993, Vol. III, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1993, no. 579-1, illustrated in colour

Catalogue Note

Masterfully orchestrated with vibrant hues of yellow, green and red through which underlays of dark pigment suspended in oil emerge and coalesce in an elegant corps a corps, this work appears as the evanescent landscape of a half-remembered dream. Demonstrating a powerful chromatic range of primaries dynamically swept across the picture plane, D.Z. is an early example of Gerhard Richter’s mature answer to the compositional challenges of abstraction.

Richter’s oeuvre is characterized by the herculean feat of challenging the medium that is the most established, aristocratic and weighed down by tradition: oil on canvas. His restless investigation into the matters of perception is conducted with such an extraordinary and seemingly limitless freedom despite its self-imposed material parergon that it indisputably crowns him as the master of contemporary painting. Described by Hans-Jakob Brun as one of the “extremely few artists on whom the focus in continuous”, his unique virtuosity led him to a phenomenal success that never tires. (Exh. Cat., Oslo, Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Gerhard Richter, the Art of the Impossible – Paintings 1964-1998, 1999, p. 6)

The artist’s homage to illustrious art historian and co-curator of the 48th Venice Biennale and Documenta IX Denys Zacharopoulos, D.Z. encapsulates on an intimate scale typical of Richter’s works from the mid to late 1980s his remarkable grasp on the foundations of our visual understanding and cognition. After decades of conceptual enquiry, the current lot lies at the crossroad of a paradigm shift in the artist’s practice – which, given Richter’s position of “incontrovertible centrality” within the canon of contemporary Art History means an outstandingly rare flicker of premonition into the future of painting and visual culture itself. (Benjamin H. D. Buchloh quoted in Exh. Cat., Cologne, Museum Ludwig, Gerhard Richter Large Abstracts, 2009, p. 9)

Over the past five decades, Richter’s practice has been driven towards the achievement of a single agenda: to find a middle ground in the dialectic between figuration and abstraction. In the corpus of his abstract works, this ambition evolved to find its resolution throughout strategies of ordered chance. Richter’s earliest experiments with complete abstraction verged either towards a cooler and systematic technique concealing evidence of the artist’s hand, which echoed a more geometric or minimalist type of abstraction such as Piet Mondrian’s or Barnett Newman’s, or on the contrary displayed spontaneous and thickly impastoed painterly gestures reminiscent of Jackson Pollock and Art Informel. These experiments conducted within the furthest recesses of abstraction resulted in the 1980s in his most celebrated body of work, the epic and ongoing Abstraktes Bilder – of which the present painting is one of the very first epitomic examples. D.Z.’s bold primary colours and sweeping layers of yellow paint tracked across the canvas by the squeegee are combined with organic and seemingly finger-painted red, bluish-grey and black accretions in a cross-like pattern. This makes of D.Z. an extraordinarily literal application of Richter’s career-defining paradoxical blend of the mechanical and the bodily, simultaneously revealing and concealing the artist’s presence.

The apotheosis of Richter’s oeuvre, the Abstraktes Bilder cross the perennial conceptual bridge between figuration and abstraction and declare it obsolete: all of Gerhard Richter’s paintings are pictures, as the abstracts evoke unrepresentable yet familiar images in the collective consciousness. Furthermore, the Abstraktes Bilder render void the primal dichotomy operated between order and chaos by bringing into form pictures that are not predetermined by the artist but whose production rely equally on spontaneous inspiration and the arbitrary accretions created by the squeegee - and D.Z. is the most fully resolved work up until that period to display evidence of Richter’s mastery of this hard-edged spatula which earned Richter early critical acclaim and later on a weight of almost canonical authority.

The present lot will be included in the forthcoming fourth Volume of the official catalogue raisonné, edited by the Gerhard Richter Archive Dresden, under nos. 716-18, 716-19, 716-20, 716-21, to be published in 2014.

Provenance

Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London

Acquired directly from the above by the present owner in 1991

Exhibited

London, Anthony d'Offay Gallery, Gerhard Richter Mirrors, 1991, pl. 5, illustrated in colour

Literature

Angelika Thill, et. al., Gerhard Richter Catalogue Raisonné 1962 - 1993, Vol. III, Ostfildern Ruit 1993, no. 716-18/19/20/21, illustrated in colour

Catalogue Note

First shown together as an ensemble alongside many of Gerhard Richter’s most spectacular works, the present four paintings represent the artist’s on-going investigation into the nature and potential of abstract painting. Abstrakte Bilder was originally part of Richter’s 1991 exhibition, Mirrors, held at Anthony d’Offay, in which the abstract works were exhibited alongside a number of diverse yet thematically linked paintings including Richter’s conceptual Four Panes of Glass from 1967, the famous Photo Painting of Richter’s daughter Betty from 1988, and a selection of Mirrors and Grey Paintings. Curated together these works illustrated the holistic nature of Richter’s oeuvre, while demonstrating the power of his abstract techniques, a facet readily apparent across the present four canvases. Numbered 716-18 through to 21, these intimately scaled paintings collectively act as an intriguing exemplar of Richter’s abstract painterly language. Imbued with sweeping grey tonalities punctuated with opalescent underlayers of crimson, green and blue, these works allow an insight into Richter’s creative practices, highlighting his ability to work simultaneously on several canvases in order to preserve the overall unity of Abstrakte Bilder. Indeed, displayed together, the appearance of these works as a whole marks a rare opportunity to fully appreciate the inner workings of Richter’s method - the product of which is today considered among the highest artistic achievements of the late Twentieth Century.

Since the very outset of his career during the early 1960s, Richter has called into question the conceptual underpinnings of painting and representation. Encompassing a variety of disparate yet thematically related painterly approaches, Richter’s career represents a cumulative inquiry into representation and abstraction in painting: positioned at the vanguard of this continuing project are the Abstrakte Bilder. As illustrated by the present works, Richter’s exploration into the field of abstraction stands distinct from both the formal and chromatic sparseness of minimalism, and the impassioned gestures of abstract expressionism. Rather, evoking the aesthetic blur of photography and immaculate cibachrome lamina of the print, Richter’s semi-automated procedure of repeatedly drawing layers of paint across the canvas with the squeegee results in a sense of harmonic painterly equilibrium.

Richter initially confronted abstract painting when he executed a group of vivacious and colourful sketches in 1976; created in 1991, the present group of small scale abstract works stem from over a decade of investigation into various technical and aesthetic abstract possibilities. The production of the Abstrakte Bilder, which to the present day still occupy the mainstay of Richter's painterly inquiry, stand as the most complex challenge of his career to date. The movement and application of the squeegee, visible in layered sweeps across the delicate tonalities of the present ensemble, indicates the true dedication of Richter’s painterly process, leading to intriguing gradations in texture and tonality. As the present works attest, Richter's abstract corpus stands as the true summation of an endlessly perpetuating creative journey.

Each individual quarter of Richter's Abstrakte Bilder is strikingly beautiful in its concentrated, miniature format. Emanating from a deep and clear understanding of the complexities of painterly abstraction in its varying illustrations, these four works embody a nuanced and ambiguous response to such formal tensions and their contrasting histories. Richter's abstraction wavers between a simultaneous negation and affirmation of the ineffability of the beyond, an idea elegantly suggested within the layers of arresting pigment that seem to give way to glimmers of an entirely alternate visual plane behind a diaphanous painterly screen: "somewhere you can't go, something you can't touch" (the artist in interview with Nicolas Serota, in Exhibition Catalogue, London, Tate Modern, Gerhard Richter: Panorama, 2011, p. 19). Ultimately Abstrakte Bilder– taken as the sum of its parts - is a masterful example of Richter’s investigations into the possibilities of pure painting: a celebration of the exciting potentials of a medium in which the artist is utterly in control.

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932ABSTRAKTES BILD signed, dated 1992 and numbered 777-2 on the reverse oil on canvas 71.8 by 61.6cm.; 28 1/4 by 24 1/4 in. |

Provenance

Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London

Private Collection, Baltimore

Sale: Sotheby's, New York, Contemporary Art, 13 May 2009, Lot 146

Acquired directly from the above by the present owner

Literature

Angelika Thill, et. al., Gerhard Richter Catalogue Raisonné: 1962-1993, Vol. III, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1993, no. 777-2, illustrated in colour

Catalogue Note

The rich, buttery smears of Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (777-2) pulsate in a rhythmic grid, highlighting the kaleidoscopic hues ranging from stark white to deep red and mossy green. The bold and vivid colors undulate in a lattice formation under the smooth, almost shimmering surface. The controlled vertical and horizontal striations of the present work clearly show Richter’s mastery of the squeegee technique at this point in his career.

The 1992 canvas was painted at the apex of Gerhard Richter’s career: the same year as he showed collection of his abstract paintings at Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany, the year after a dedicated exhibition of his work at the Tate Gallery, and a year before Richter’s first touring retrospective exhibition. Facing a newfound celebrity, Richter approached his canvases of this era with a renewed confidence and prowess in his squeegee technique, yet still regarded his oeuvre with a self-critical eye, always harshly judging each work.

In 1992, Richter began a thorough exploration of gridded compositions in his abstract paintings, ranging in size and color. These grids seem to recall his Colour Chart paintings from the 1970s, which displayed a myriad of color samples in grids of varying size. Richter’s grids also pay homage to Modern master Piet Mondrian’s radically abstract geometric paintings. In Mondrian’s stylistic explorations of the early 20th century, he ultimately found the purest form of abstraction to be the grid. Mondrian harnessed blocks of primary color inside of the intersecting vertical and horizontal lines on rectangular or rhomboidal canvases. In 1998, Richter looked to Mondrian’s diamond-shaped canvases in the Abstraktes Bild (851) series of six works, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston. Though Richter closely studied his predecessor’s aesthetic, Mondrian’s exact, meticulous and minimalist aesthetic stands in stark contrast to Richter’s giant, energetic smears of vibrant colour.

Two decades after the Colour Chart paintings, while fully entrenched in his abstract aesthetic, Richter returns to his earlier color exploration. What renders the latticework of the 1992 abstraktes bilder unique from the Colour Charts is Richter’s relinquishing of a precise, detail-oriented technique with total control. Although Richter demonstrated acute skill and dexterity with his squeegee in 1992, the method is constantly subject to slippages, creating unplanned mistakes in the final canvas. In an interview with Sabine Schütz, Richter confesses, “I want to end up with a picture I haven’t planned. This method of arbitrary choice, chance, inspiration and destruction may produce a specific type of picture, but it never produces a predetermined picture…I just want to get something more interesting out of it than those things I can think out for myself” (the artist quoted in: Gerhard Richter: Text, Writings, Interviews and Letters 1961-2007, 2009, p. 256)

Indeed, Richter’s final composition ultimately ends up surprising him. Richter begins his process by placing white, primed canvases around his studio, attacking each one with squeegee strokes, layering them until he decides the work is finished. Often Richter leaves a work hanging in his studio, only to decide days or weeks later that the work must be revisited or that the work is finished. Richter describes his process: “Over time, they change. In the end, you become like a chess player. It takes me longer than some people to recognize their quality, their situation – to realize when they are finished. Finally, one day I enter the room and say ‘checkmate’”(the artist quoted in: Michael Kimmelman, "Gerhard Richter: An Artist Beyond Isms," New York Times, January 27, 2002).

Though thoroughly and entirely abstract, Richter confesses that his abstraktes bilder are not devoid of figuration. Indeed, Richter believes that even his most abstract works may reference the visual world. “Almost all the abstract paintings show scenarios, surroundings and landscapes that don’t exist., but they could create the impression that they could exist. As though they were photographs of scenarios and regions that have never been seen” (the artist quoted in: Exhibition Catalogue, London, Tate Modern, Gerhard Richter: Panorama, 2011, p. 19). Upon close inspection, forms appear to emerge from the present work: perhaps trees, windows, or skyscrapers, all seen in a blur of motion or even memory. This blurred effect makes reference to Richter’s photo-based painting style that he has weaved throughout his entire career. Subsequently, Abstraktes Bild (777-2) references Richter’s diverse aesthetic and range of styles from his earlier oeuvre in a beautiful amalgamation of colours, textures and lines.

|

Gerhard RichterB.1932ABSTRAKTES BILD signed and dated 1991 on the reverse oil on canvas 41 by 51cm.; 16 1/8 by 20in. |

Friday 8 February 2013

Wednesday 6 February 2013

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

7,000,000 - 9,000,000 GBP [L. 7]

7,000,000 - 9,000,000 GBP [L. 7]